Two Works That Caught my Attention This Week

Over the past week I encountered two works that caught my attention. One was during a critique session at UVic when Nic Vandergugten presented a video installation of Tree Climb the other was over a coffee with Trudi Lynn Smith as we talked about her ongoing project Trouble With Trematodes.

Tree Climb, is a several minute floor to ceiling video projection that repeats. In the video the camera is directed at a tree in the west coast rainforest. This particular tree stands apart due to its formidable grandness and artistic beauty. Reminiscent of Emily Carr’s Scorned as Timber, Beloved of the Sky, its very tall and stately trunk is bare of greenery with the exception of a very large clump near the top. A young man enters the frame dressed in a red plaid jacket and attempts to climb the tree. Awkwardly, he appears to be trying to reach the upper branches. Some twenty feet up he seems unable to climb any higher and after some moments of looking around searchingly, he haltingly and nervously descends.

References to the west coast narrative of economic politics, logging, the lumberjack and rainforest are apparent but this plaid-coated young man is of another history and a different, perhaps competing story. He is not a logger and appears drawn to this tree for less than pragmatic reasons. Perhaps it is the tree’s aesthetic beauty, its mythic, magical or spiritual powers that interests him? His mission seems to be driven by a desire to reach and perhaps be immersed in the tangle of greenness atop this tree. Yet this video represents the impossibility of this desire and his ultimately failed mission.

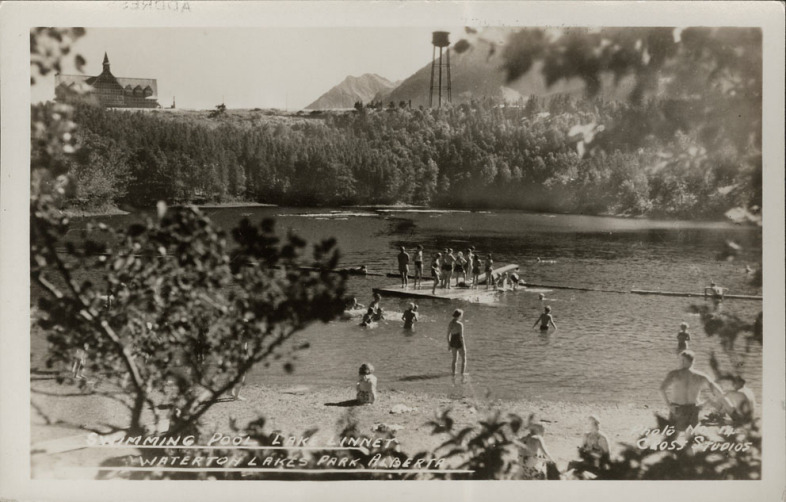

The Trouble With Trematodes[1] (a work currently in progress) is comprised of three parts, 1. a phenakistoscope (a variant of the zoetrope) on a plinth adjacent to a wall mounted mirror, 2. a postcard mounted on the wall and 3. an academic paper on a small table with chair. Using the hand held phenakistoscope and looking into the mirror, the viewer sees a repeating ‘film’ of a swimmer crossing a lake (Linnet Lake, Waterton National Park) at dusk. The postcard (circa 1930) is also of Linnet Lake and depicts children playing, swimming and jumping off a dock.

Although both, represent swimmers at Linnet Lake, the postcard shows a typical family holiday photograph, while the phenakistoscopic image depicts a different scene. Here we have a somewhat somber and haunting image. Dusk is setting and this swimmer is alone. The water is dark and there is a sense of foreboding. We cannot identify this ghostly swimmer and the camera surveils from the shore at a distance. The swimmer’s movements are calculated and directed. We are not privy to a departure or destination point nor are we informed as to the relationship between the swimmer and the filmmaker. Instead we are left with a narrative that is severed and disturbing.

In the third part of Smith’s piece, the academic paper, she moves from filmmaker to ethnographer. Here narrative and stories abound. Smith researches archival photographs and conducts interviews with people who swam in Linnet Lake, to recount an interconnected relationship between people, pathways, ideas, class, government, migratory birds, water and parasites as non-oppositional agents on the move.

[1] Flatworm parasites often found in lakes